I asked my friend Chelsea to measure my height. She asked me why. I didn’t want to tell her. I didn’t want to say, “I want you to measure me in inches, so that I can convert that number to shaku, and figure out how long my first iaito should be.”

I asked my friend Chelsea to measure my height. She asked me why. I didn’t want to tell her. I didn’t want to say, “I want you to measure me in inches, so that I can convert that number to shaku, and figure out how long my first iaito should be.”

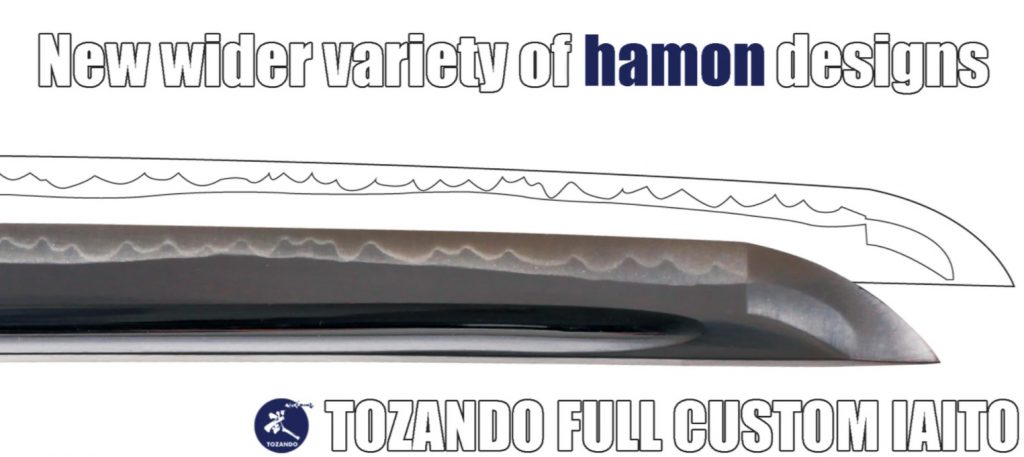

If I said all that, I knew she’d have questions: “What does shaku mean? What’s an iaito?” she’d ask, and I’d tell her, “Shaku are a Japanese unit of measurement, and an iaito is a Japanese training sword.”

“Like, a samurai sword?” she’d say.

“Yeah. Like a samurai sword.”

I didn’t want to have that conversation. But why?

We rightly live in a time of heightened sensitivity to the power dynamics and histories among different cultures. The concept of cultural appropriation—that is, to adopt the practices and, often, the clothing of a culture different than your own without the deep knowledge that a native would have, resulting in a caricature of the culture in question—is well known among many people.

I admire my friend Chelsea for being well-versed in progressive politics, including cultural appropriation. So, in short, I didn’t want to tell her about shaku and iaito because I didn’t want her to know that I practice Iaido—which is to say, I didn’t want her to think of me as the straight white guy that I am, wearing a hakama, playing with swords, and pretending to be Japanese. I told her I needed my height in inches for a suite coat that needed tailoring and slouched off.

I lied to Chelsea, and I don’t think lying comports with the martial arts. It doesn’t comport with the Way. But my embarrassment at telling people of my secret passion for Iaido is, I think, rooted in a genuine ethical dilemma: How can I respectfully participate in a centuries-old tradition like Iaido with no ties whatsoever to Japanese culture?

I mean, I was born in the country that produced “The Last Samurai,” a white-savior movie starring Tom Cruise as a Caucasian man who goes to war in Japan and becomes—surprise, surprise—pretty much the best samurai around. And, honestly, I loved that movie when it came out, and I still like it today. So how can I escape from it? How can I deepen my knowledge and appreciation of Iaido?

My first idea was to read books about swordsmanship. I started with Yagyu Munenori’s The Life-Giving Sword. Sadly, it was almost totally inaccessible to me: filled with techniques and stances named for rivers and mountains, I understood I was encountering a manual created specifically for the swordsmen of its time, not a 21st-century American at the beginning of his journey to learn the Way.

Add to that the fact that translation from one language to another— Japanese to English in this case—inevitably changes meaning, and I was left feeling like an archeologist interpreting cave paintings. Nonetheless, I read the whole thing, absorbing as much as I could. Think of someone wringing out a damp rag for a few drops of water.

One evening at the dojo it was just me and my sensei, Patrick Chase. We often talk after class, and that evening I told him about the trouble I’d had reading The Life-Giving Sword. Chase Sensei was sympathetic to my dilemma, but he told me that the deeper, truer learning comes from training, that the philosophy of Iaido was contained in the techniques themselves.

Reading, he said, was a useful supplement to actual practice, but that it would never impart the kind of understanding of that I was looking for.

“What a relief,” I thought. “Just keep training, and stop worrying about Tom Cruise!”

A child of the 1960s and an accomplished classical guitarist and martial artist, as well as a practitioner of Vipassana meditation, Chase Sensei is a teacher whose insight and thoughtfulness I’ve quickly come to rely on. He’s an American, like me, and so perhaps is just as problematically distanced from Japanese history and culture as I am. But—and I know this is hardly an academic justification—I feel like Chase Sensei is the best teacher for me, no matter his background, and so I’m left with no choice but to gratefully trust in his instruction, his wisdom, and—most importantly to me—his good and decent character. If ultimately, to some, we’re both a kind of Tom Cruise, well, haters be damned.

Someone might say, “Timothy, if you’re so worried about cultural appropriation, why don’t you just learn more about Japanese culture?”

“Good point,” I’d answer, and I’m going to try to do just that—starting with learning some Japanese.

There’s a theory in linguistics that goes something like this: the language you speak shapes your reality. So, if you’re, say, a native speaker of French, this theory says you experience the world in certain ways that only your fellow French speakers can comprehend.

Likewise with English, Arabic, or any other language you could name. Many modern linguists no longer support this theory, but it still has defenders in the academy, and I find it compelling and plausible (though I also believe human nature is fairly universal, and there’s no feeling we can’t all relate to on some level). Going by this theory, then, it stands to reason that learning Japanese will help deepen my understanding of the Way. So I’m going to try.

Trusting my teacher, committing to training, learning Japanese—none of it will magically turn me into a bugeisha of old. I’ll always be me, born Caucasian, born an American, born in the 20th century, born a Tom Cruise. I’m okay with that. My culture, like every culture, is rich and contains its own mysteries worth pondering.

I believe I’m on the right path, or I hope I’m on my way to finding it. And there’s a final idea that gives me some comfort: the journey of the martial artist has no end. No matter who you are, or when you were born, the Way has no final destination. We all remain, eternally, at the beginning of an infinite journey.

by Timothy Slover(Tozando Essay Contest winner 2017)