Kizu is the evidence of repeated forging

The Japanese sword is primarily composed of tamahagane (steel made from iron or black sand). As it is forged repeatedly, there are cases where impurities are not completely removed or small mistakes during the forging and tempering process can cause kizu (flaws) in the sword. This kizu may cause problems during actual use and for authentication. Recently the sword is valued more as an artwork for appreciation rather than its actual use. There are certain types of kizu that are actually appreciated for their beauty.

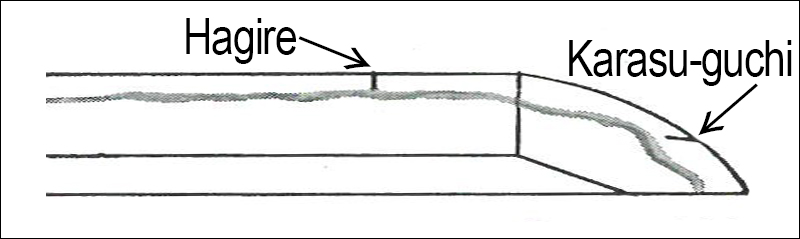

Hagire/Karasu-guchi

When a crack appears in the tempered edge and extends to the blade it is called hagire. When that hagire is at the tip of the sword it is called karasu-guchi or a “crow’s beak.” Practically speaking, these can be quite detrimental in using the sword, but this is not considered a draw-back for swords that are meant to be display items.

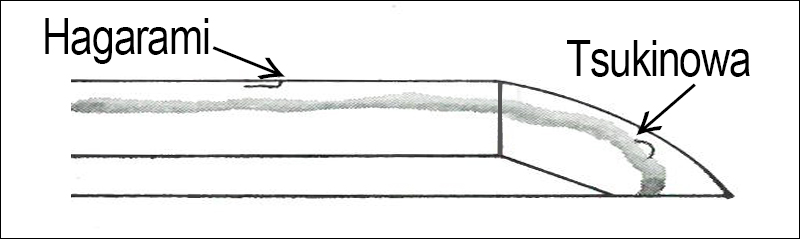

Hagarami/Tsukinowa

The cracks that appear along the forged surface are called hagarami. If this appears near to the sword point it is called mikazuki or “crescent moon.” This can appear on both sides or just one side of the blade. It is a defect, but in Japan, it has long been called tsukinowa or the “ring of the moon.” This attractive manner of naming these defects shows a long held tradition in Japan to see imperfection as a large part of the whole of an object and thus something to be admired for its aesthetic beauty, if not for its practicality.

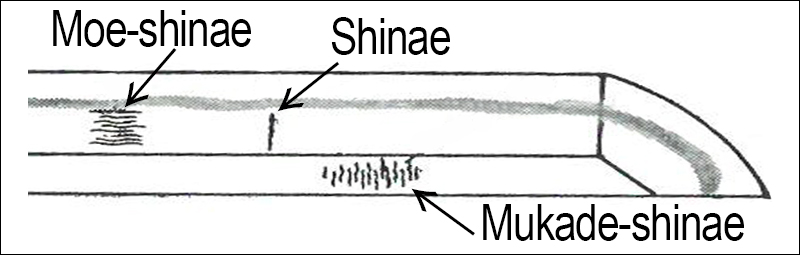

Shinae

If you are to look at a sword carefully, you can see some lines on the base, blade, and ridge. These are called shinae. When may of these lines are formed together they become mukade-shinae or “centipede-shinae”. When they are of an almost smoky color and appearance, they are known as moe-shinae. In all these cases, the shinae are imperfections that can create a blade vulnerable to bending and stress and therefore not one that you would want when fending off an adversary.

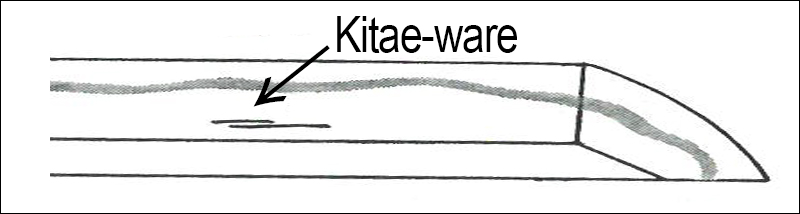

Kitae-ware

These very small tears can appear if the steel layers have not completely welded together during the tempering process. This imperfection is known as kitae-ware and can appear on the blade, base, and on the ridge of a sword. Usually, it appears as a hard break so, unless it is rather large, it will generally not impede its practical use. For straight-grain swords or strong swords with a straight-grain mix, these are called masa-ware and are not considered defects. In Hankei swords, they are considered common traits of those swords and not flaws at all.

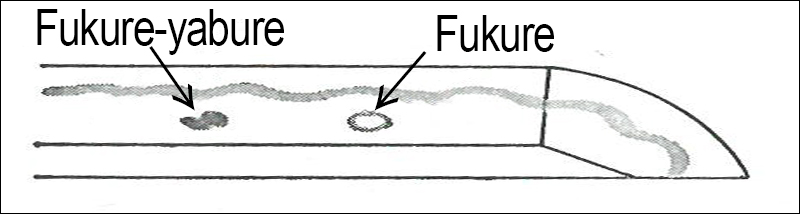

Fukure

During the tempering process, should the welding of the metal layers be insufficient, bubbles can occur within the blade. It may swell in the area to the size of a small bean. This is known as fukure and should it break during the sharpening process it is known as fukure-yabure or the “tearing of the fukure“. This can expose rusted iron inside the cavity, which is disliked and would depreciate the value of a sword. Although these will not likely affect the structural integrity of the sword, they are generally disliked for their appearance and would thus make the sword less attractive.

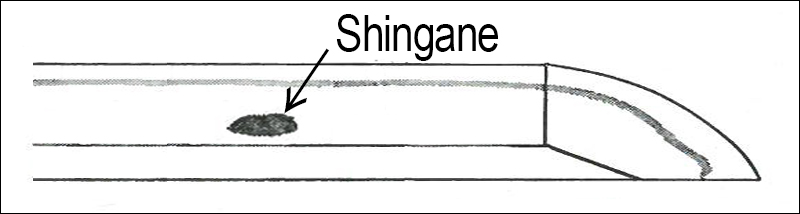

Shingane

The shingane or “inner iron” appears when the sword is sharpened excessively and the outer steel layer is lost. Should a sword be made by an inexperienced smith or be a large scale production sword, the shingane can often be seen from the very beginning of the swords life. These swords are considered inferior items. The Rai school of sword smithing, however, will often have these marks around the blade. This is due to the shingane being placed in a bend and not in a straight line as is done with other smithing schools. It becomes exposed when the outer steel layer is sharpened. In this case, as the other side is kept very neat, this is called Rai-jigane and is a common trait of the Rai school.

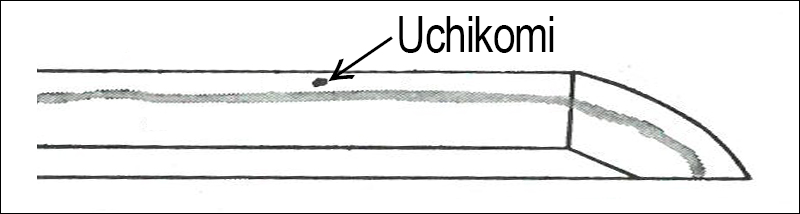

Uchikomi

Around the blade, base, or the ridge, there may appear a small, almost perfectly round hole that would appear to have been made by a drill. This is formed by the oxidized iron from the outer layer falling off during the refining process. The inner layer mixes with the outer layer and escapes the interior of the sword. This is called uchikomi and has no impediment in practical use for the sword, but does lose some aesthetic quality.

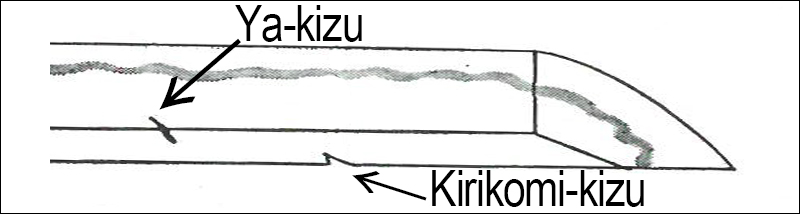

Ya-kizu/Kirikomi-kizu

These marks, which appear from cutting down arrows, are called ya-kizu. Those that appear after clashing against an opponent’s swords are called kirikomi-kizu. They are indeed flaws, but are not considered defects. They are in fact appreciated. Some kirikomi-kizu include some where shards of the blade of the opponent’s sword have become lodged in the blade. These flaws tell the story that the sword has lived, and in its time taken on battle. In fact, with no other imperfections other than these flaws, the sword has shown its durability and strength under extreme duress. These types of flaws were thus very highly regarded by the samurai who would depend on such a well crafted sword for their very lives.

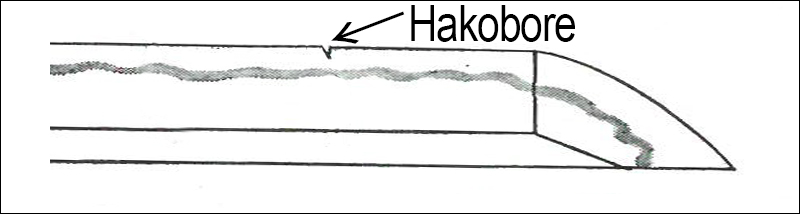

Hakobore

Like ya-kizu and kirikomikizu, hakobore are incurred during battle when an impact on a hard surface causes the blade to be chipped. This type of flaw will, however, depreciate the value of the sword greatly due to the impediment on both its practical use and aesthetic quality.

As with most all art in the world, the aesthetic quality of an item is wholly up to the beholder. The Japanese phrase Ju-nin To-iro means “Ten people, ten colors.” Or, “To each their own.” When it comes to practicality with these weapons however, with your very life on the line, one man’s trash is most certainly not another man’s treasure.

| Did you like what you've just read? Check this out. |