We have another of our essay contest winning entries to kick off this week. In this article Arash explores how his connection to Japanese budo developed and also shows how it now manifests in his sons. We all have our own experiences with discovering budo, like Arash, many of us did it alone. It is interesting now to see new generations exposed in a similar manner to children in Japan.

Cultural transmission

I first encountered Japanese culture when I was introduced to Akira Kurosawa’s Samurai films, which turned into a lifelong fascination.

In the early 1980s, when I was a young boy, Iran went through significant changes, when the revolution of 1979 was followed by a war. Governments often seek to distract populations from the hardships of war by offering entertainment. In a similar move, the state TV of Iran flooded the screens of the war-torn country with Japanese films, in particular samurai films. Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and some of his other masterpieces were played nearly every weekend.

At the time, I was of course unaware of the artistic significance of Kurosawa and other Japanese directors. But carving wooden swords and enacting Samurai fighting scenes were top priority for me and my friends, at times our only entertainment in a distressed environment.

In the mid 1980s, our family emigrated to Germany and there I re-discovered, much to my parent’s dislike, Kurosawa’s œuvre. For a while, these films had fascinated me and my childhood friends; the constant repetition of the same films had apparently bored the adults. In Germany, however, I also discovered new aspects of Japanese culture. For instance, Yoshida Kenkō’s fascinating Tsurezuregusa, which remains one of my most treasured reading experiences: it introduced me to the aesthetics of minimalism, the art of Haiku and most significantly, to Zen Buddhism.

I became every parent’s nightmare by announcing as a young adult that I was renouncing the world as we know it for a move to Japan, where I wished to become a Zen monk. Luckily for my parents, I never realised this plan despite my strongly felt desires. I remember very well the many sleepless nights that I caused them and myself. Many years later, I saw myself reflected in the writings of the author Janwillem van de Wetering, who describes his attempt to study Zen in Japan with much honesty and humour.

An ever-present current

As the years have passed, I have encountered many different aspects of Ja-pan’s immensely rich culture. Taking up Kendo is my most recent exploration of this magnetically absorbing culture. I do not maintain a romanticised image of the Samurai culture and understand the historical development of the Japanese society and the position of the Samurai class within it. I associate Kendo not just with physical exercise, but also as a chance to improve various skills by immersing myself in the study of the art of the sword.

As a historian, I feel at home when I read about Japan’s past through engagement with Budo and greatly enjoy works such as Alexander Bennett’s most recent publication on Miyamoto Musashi’s texts, manuscripts and life. Despite all that, and perhaps more importantly, Kendo allows me to go back to the naive imaginations of my childhood that seem lost amidst social upheaval, war and emigration. Thirty and some years after I first watched Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai as a young boy, the Shinai and the Bokuto replace the wooden swords of my childhood, and I see Toshiro Mifune’s unforgettable performances in front of my eyes.

Passing on your passion

A major difference between my earlier forays into Japan’s culture and now is that this time I am not alone: Japanese culture and Kendo play a signific-ant role in our family life. My older son, Hourmazd and his younger brother, Siavash, have long been fans of Hayao Miyazaki and enjoy watching his an-imations. They also appreciate Manga and Anime productions.

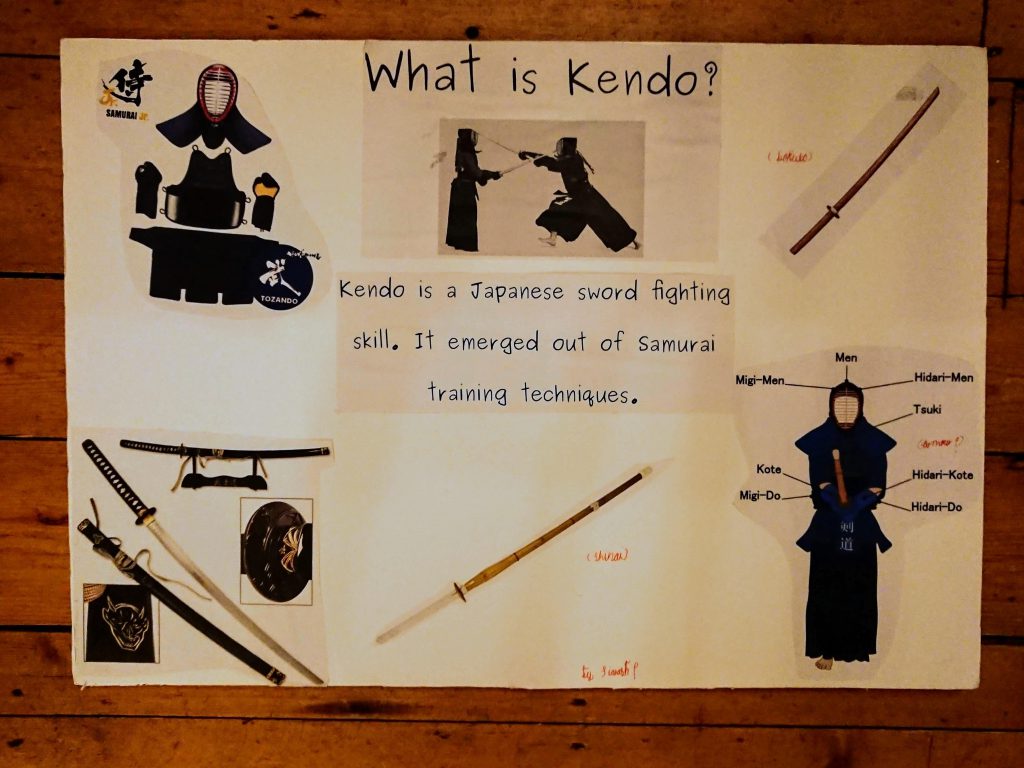

Together they purchased the whole series of the Rurouni Kenshin Manga. Siavash is reading his way through the entire set and is always very excited when he finds aspects of Kendo in the books. Meanwhile, Hourmazd is patiently waiting for his turn to read the series. Siavash recently chose Japanese as the language of the week at school and made a poster about Kendo for his class.

When I asked him to install the German module in the language learning app Duolingo, I caught him secretly exploring Japanese in an attempt to learn the language. His greatest wish and most frequently asked question is when we can travel to Japan. Both of them have written a little piece on Kendo which I reproduce below without making changes to their texts.

We practise Kendo together in Cambridge, and it offers us more than phys-ical exercise. We learn, as a family, new ways and views of life. The children learn respect towards their teachers, the importance of discipline and dedication. They also experience the challenges of striving for a goal and the positive feeling of achievement. Iranian culture, as I know and experienced it, greatly emphasises respect towards the elders of the community.

I strongly hope that Hourmazd and Siavash better understand their Iranian background by studying discipline, humility and respect as taught and practised in Kendo. Perhaps the guardians of the Iranian state TV understood more than the adults gave them credit for, at the time when they introduced Japanese movies to us.

Kendo and what it means to me!

– Hourmazd Zeini

‘I started Kendo because I wanted to achieve a higher level of fitness, and I enjoy Japanese culture such as anime and manga. I hope to one day start Iaido and practise with a real Katana. My Father and Brother also practise Kendo, and we train in Futoku-Kai Dojo in Cambridge with a 4th dan sensei. One of my favourite parts of Kendo is learning the ancient Katas, which I like because in a way it is a contrast to Kendo. Kendo is all about moving quickly, training, and fighting your opponent, but the Katas are similar to meditation. In the Katas you move slowly and take the time to notice what you are doing wrong and how to improve. I also enjoy learning the past of Kendo and Japan.’

What Kendo means to me!

– Siavash Zeini

‘I enjoy Kendo because it’s interesting and it inspires me to read and watch manga and anime. When my dad introduced me to Kendo I immediately started to read this manga called Rurouni Kenshin. The only thing Kendo means to me is joy and happiness. And Kendo brings to me a Katana that is my goal I am trying to achieve. I like the way of the sword because it’s cool and I like to practise the ancient Katas and Japan’s Kendo styles.

I also enjoy Kendo because it brings me together with my brother and father. When I do Kendo I feel lots of joy and happiness and I when I’ve finished Kendo I feel sadness because the happiness is over. When I go home from Kendo I try to embrace the feeling that I absolutely love Kendo. When I do Kendo I feel so lucky because it was banned in Japan and feel so good that Kendo was released again and in Japan it’s really common. In Kendo I try to do the best I can and I try not to fail. I am not even close to my goal. My dad is in Bogu, I am not even in Hakama yet.

I am still practising every other Sunday in Cambridge. My sensei is very kind, and he also tries his best at Kendo. When I watch sensei I am amazed how good he is and I know I can be perfect like him some day. I don’t know when, but I do know I will be like him. So I just want to become good and achieve my goal soon enough that I am not old! I wish you the best of luck with Kendo and you should try your best at it. I am sure you will achieve your goal, if you have one anyway.’

by Arash Zeini, with excerpts form Hourmazd Zeini and Siavash Zeini

| Did you like what you've just read? Check this out. |