When people think of the samurai, the weapon that immediately comes to mind is their curved sword, the katana. Some people would also think of the naginata – a weapon that was used widely by the samurai for many years and played a key battlefield role. In this article we take a look at the characteristics of this famous samurai weapon, it’s history, use in battle and how it survives today.

Just like the katana, the naginata conjures up many images of feudal Japan: the dedicated footsoldier, the heroic onna-bushi and also the devout warrior-monk to name but a few. Whilst grounded in truth, these perceptions have warped our image of the naginata and its use perhaps more so than any other traditional Japanese weapon. To many, the naginata and its accompanying ryu-ha are “feminine” or the sole domain of the warrior-monks. This is far from the case!

Form

First off let’s take a look at the characteristics of the weapon itself. It consists of two main components: a long curved blade and the shaft the blade is mounted upon. The length of the blade and shaft could vary, but in general the naginata as a whole would be between 210cm and 250cm long. It had to be long enough to give the user a significant reach and power advantage over a sword, but not be so long as to be unusable.

The blades of naginata were made in the same way as katana were, folding hard and soft steel together. They feature many of the same specialities, like hamon and so on. Just like katana, these blades came with different curvatures and shapes depending on the predilections of the smiths at the time they were made. Naginata blades would be attached to their shafts with a long tang and mekugi peg in a similar manner as katana. The shaft would then be bound with materials to clamp the shaft around the tang to make the blade incredibly difficult to remove or snap off.

The shaft of naginata were characterised by their oval shape aligned to the cutting edge, just like the tsuka of a katana. This allowed the user to not only leverage the weight and power of the naginata efficiently, but also meant that you easily tell the orientation of the cutting edge through feeling alone. This was crucial when using a long hafted weapon where you move your hands constantly to change position. The end of the shaft was capped with metal, this was called an ishi-tzuki (literally stone-piercer) – this reinforced the haft and allowed the user to thrust with either end of the weapon.

The naginata gives its user the abilty to control the space around them. Combining the versatility with the deadly blade of a sword that could both stab and thrust made them formidable weapons. However to use a naginata to its full potential you must have the space to make long powerful sweeps. These characteristics made the naginata very effective against cavalry as well as unmounted warriors armed with swords.

Where did they come from?

When you first look at the naginata it is very easy to identify it with a spear or other polearms. However it is thought that they were actually developed from swords. This can be seen first of all in their construction, they share a similar tang style mount rather than being socketed like the early spears used in Japan called hoko.

Some scholars suggest that the first naginata were improvised weapons made by foot soldiers whose spears had been broken and desperately tied sword blades to the ends of the headless hafts.

It seemed the need for the naginata as a weapon arose as elite, mounted bushi armed with bows and tachi rose to prominence. In these skirmishes the space to use the naginata was readily available and its length as weapon was incredibly valuable in de-horsing opponents. They were not only useful against cavalry their ability to cut through armour combined with a deadly reach made them very effective in the dispersed formations of infantry that were popular in battles at the time.

Decline

The naginata remained in use to the very end of feudal warfare in Japan, but whilst it dominated the early battlefields of Japan, as warfare grew to encompass more and more people its popularity amongst foot troops waned somewhat. With the increase in conscription and use of peasant ashigaru regiments, battlefields became more and more packed with formations and individual combat became more and more cramped. This meant that the naginata was surpassed by the simpler yari in later eras.

Legendary Associations

If you ask many Japanese people ‘who’ you associate with the naginata their first answer will undoubtedly be women. After that you might get some people who will say buddhist warrior-monks (sohei). This is often enough to give many people the idea that the naginata was not used by anyone else.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. Historically the naginata has been used by all sorts of people from many levels of Japanese society. However, because the sword was fetishised by the ruling male class of the time and they were the main subject of the histories, literature and art the naginata would rarely appear under normal circumstances. Consequently the characters that supported these male aristocrats – noble women and buddhist priests were often seen depicted with the naginata. Despite its ubiquity as a battlefield weapon.

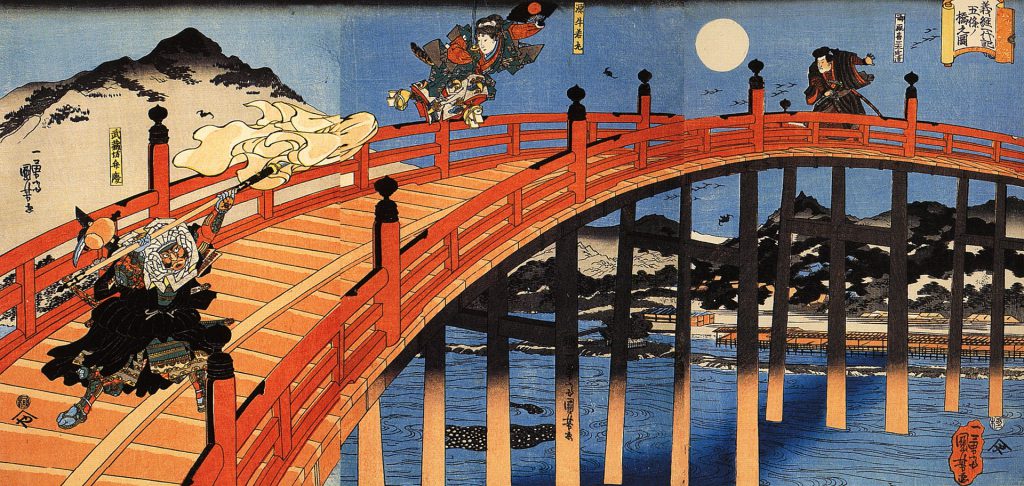

Wealthy samurai women were trained in martial arts as part of their education. They were as likely to be as well versed in kenjutsu as they were naginatajutsu. However as the naginata was seen as equalising the stature advantage men had over women of the time, female warriors were often depicted with the naginata. None is more famous than Tomoe Gozen (the mounted naginata wielding warrior featured at the very top of this article!).

Sohei – Warrior Monks

The warrior monks of feudal Japan (sometimes called sohei), are also often depicted with naginata. In reality they used a whole variety of weapons, from swords to spears, iron bound clubs (tetsubo), bows and even matchlocks. Some believe that the mountainous monasteries of the buddhist devotees favoured the use of the naginata. Its reach and weight letting you quickly control the distance and defeat your enemy quickly. However really the warrior-monks probably fought just like any other warrior of the era.

Another reason is perhaps the popularity of particularly famous warriors-monks popularised in folklore. One of the most famous has to be Benkei. This legendary warrior was renowned for his strength and loyalty. Benkei is depicted wielding a variety of weapons in art, though many place a naginata in his hands. This contrasts well with his famous lord Minamoto Yoshitsune – a war hero renowned for his swordsmanship. Here we can see the naginata relegated to a supporting character whilst the sword takes the spotlight along side the leading-man as it were.

Surviving the Meiji Era

In 1868 Japan underwent a period of unprecedented change as it embraced international modernity after the collapse of the Tokugawa government. With the restoration of the Emperor and modernisation of the armed forces; samurai were increasingly regarded as relics. Eventually the caste would be banned entirely.

The varied martial arts of Japan struggled to survive, but some koryu (old martial arts) practitioners hosted showcases and competitions to keep their arts alive. Most famously, this resulted in the renewed interest in kenjutsu. However, alongside the many kenjutsu practitioners there were also prominent naginata devotees, both men and women.

These displays were known as gekiken and drew a large amount of attention and eventually led to the integration of talented koryu teachers into the police force. This institutionalisation would result in what we see today as kendo (arising from Kenjutsu) and naginata (arising from Naginatajutsu). Before these gendai budo were entirely formalised they were even rolled out into the school curriculum. Kendo was used in physical education of boys, whilst naginata was taught to girls. This further soldified the feminine connotation that naginata still holds today.

Naginata Today

Nowadays naginata practice survives as both a gendai budo and preserved koryu tradition. Whilst many people often conflate naginata and kendo with their respective origins it is important to remember the variety of stlyes that use the naginata.

It is used as the principle weapon in many traditional koryu styles like Tendo-ryu and Jikishinkage-yu. However there many other famous ryu-ha (styles) that incorporate the naginata into their curriculum. Katori Shinto-ryu and Takenouchi-ryu are jsut two prominent examples. These sogo bujutsu (comprehensive martial arts) often spring from the early years of Japanese warfare and the naginata stands out as a defining and powerful weapon.

Slowly naginata is growing across the world with practitoners of both genders. We hope this article sheds a little light onto the magnificent weapon that is the naginata!

| Did you like what you've just read? Check this out. |