Kendo bogu breaks down into Men, Do, Tare and Kote. Amongst these components, the Kote are particularly known for wearing out the fastest. As a matter of fact, by the time you wear one breastplate out, you’ll probably have already eaten your way through three sets of gloves.

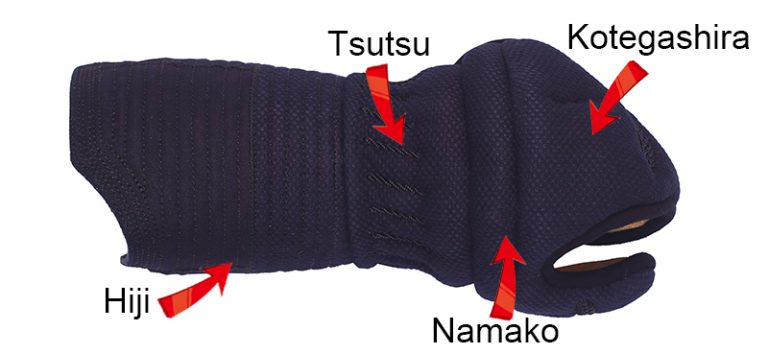

The main components that roughly make up the Kote, starting from the top moving down, are the kotegashira, the namako, the tsutsu, and the hiji, with the te-no-uchi being the palms on the reverse side. While the preferred material of choice for the kotegashira is usually deer hide, textile fabric and synthetic leather are also common. And while real leather is known to be durable, it’s a natural material after all, and it can be hit or miss. On the other hand, textile fabric is rather consistent, it’s easy to mend, and above all, it’s quick to dry. This is then filled with core materials such as deer fur or cotton. Despite deer fur being known to provide excellent cushioning and have a good sweat absorption rate, we’re seeing more cotton processed with antibacterial agents being used. This is mainly due to cost as deer-hair still provides the best performance by far.

The namako, also known as the kera, is the part of the glove that protects the part of your fist before your wrist. It’s the section found in between the kotegashira and the tsutsu, and can be designed to have one or two tiers, or can be left out of the design altogether. The advantages of having the namako are that it gives you better grip, while also allowing for optimal movement of the wrist. In Japan the trend is currently to have one namako, from our experience two namako tend not to make a tangible difference to maneuverability.

The hiji, more commonly known as the kote buton, is filled with a variety of mateirals – the most prestitgious being scarlet mousen ( a red felt spun from goat or deer hair), but cotton felt and other mateirals can be used as well. The length of the hiji varies from one region to the next and also down to the practitioner and artisan. In olden times, they were longer in the Kanto region and shorter in the Kansai region. However, since shorter gloves provide a smaller target area, this proves an advantage, and nowadays, they are made predominantly shorter throughout most of the country. Whilst obviously effective in shiai this is not recommended for serious keiko practitioners.

Te-no-uchi is the area covering the palm of the hand, and it’s the part of the glove that comes into contact with the shinai. Either deer hide or artificial leather is used for this. In the case of deer hide, it’s often smoke-processed to make it slip-free and soft. However, it’s only fault is that sweat hardens it over time. On the other hand, artificial leather doesn’t harden easily, but it’s more slippery and it brushes up with usage. So, both materials has its pros and cons. A good way to rpeserve the life of deerskin palms is to unfurl the kote after practice to reduce wrinkles and hang from the head so that sweat drains away from the palms.

Before we move on, it’s worth understanding why Kendo gloves are designed like boxing gloves, that is, when you put them on, your thumb is separated from the rest of your fingers. In comparison, gloves used in Naginata-do are designed so that both your thumb and index finger are separated from all the others fingers, and the remaining three are clustered together. However, in Naginata-do, opponents tend to keep a relatively wide distance from each other. Whereas in Kendo, when swordsmen clash up close – either when crossing swords or when colliding body to body – there’s a lot more physical contact. Bearing this in mind, previous generations most likely designed Kendo gloves with only the thumb placed separately from the other four so as to avoid injuries caused by poking each other with the other fingers. Truth be told, there’s a type of Kendo gloves in circulation with all five fingers separated, but they’re not that widespread, and after all, the conventional model is the most suitable one. The practice of Jukendo also uses a special kote. These are similar to Kendo Kote superficially, but feature different padding due to the change in kamae – the wrist joint in particular is reinforced to protect against the strong thrusts and clashes you receive in Jukendo.

Now, if we look at gloves in terms of how they fit, sometimes we see models that fasten the wrist tightly in place, with the area leading to the elbow left open. In such circumstances, not enough space is left around the wrist to mitigate impact, and getting hit there with the shinai can be quite painful. Moreover, when the glove widens, it may affect the way you deliver repeated techniques as well as the look of the glove, while it’s not uncommon for constant rubbing of the widened area to cause damage. The ideal glove sees that the whole hand fits in comfortably. Some space is left around the wrist and the glove keeps the arm straight all the way up to the elbow.

Even gloves that are produced with the same materials may vary greatly in price. Factors that impact this include the type of stitching, the namako, the number of layers in the kotegashira, as well as how elaborately embellished they are. What’s more, other discerning factors include different grades of the same deer skin, the level of craftsmanship, and the amount of work poured into making the gloves.

As mentioned earlier, kote tend to wear out fast. In order to ensure that your gloves last you a long time, one precaution you can take is to wear them snugly. After usage, make sure you wipe them clean and let them dry off in the shade. Recently, we’re also starting to see gloves that can be machine-washed. But all it takes is to get the machine settings wrong, and the gloves’ shape may collapse or the fiber may be damaged. So, it’s important to make sure you handle machine-washable gloves carefully as well.

The type of damage kote suffer from the most are holes in the te-no-uchi area. If the holes are small, there’s a way to mend this by cutting pieces of treated leather from used up shinai and patching the holes. There are times when this requires a designated needle and other tools for the job , so you’re always better off requesting repairs at a specialized store.

You might ask; “what are the points to look out for when purchasing new gloves?” Since this is the part of your Kendo bogu that comes into direct contact with the shinai, make sure you choose kote that are a perfect fit. Since you’ll find Kote with kotegashira and te-no-uchi, both made with either real leather or artificial leather, if you’re going to go with real leather, it might be best to choose a slightly smaller fit. This is because over time, the leather will stretch somewhat.

Here at Tozando, our bogu craftsmen pride themselves in being part of a tradition of Kendo bogu manufacturing that dates back well over 40 years. Our staff are all connoisseurs starting with a 7th dan master Kenshi and including other adept practitioners. Feel free to contact us with any queries as we’re confident we can assist you in the best way possible.

| Did you like what you've just read? Check this out. |