The sharp point of a Japanese katana is called the “kissaki”. It is sometimes also called the “boshi” – hat, but boshi can refer to the kissaki itself or the hamon (temper pattern) that spills onto the kissaki. Kissaki is used more often to avoid this confusion, it is also the terminology most often used in martial arts practice.

When buying and selling Japanese katana; any gashes, marks, or flaws will surely count against the sword in its evaluation. However, whether the flaws are in the body of the sword or at in kissaki makes a huge difference. A common analogy is that the kissaki is the face of the sword, so it is better to have wounds across your body than on your face. Interestingly enough, swords with no identifiable forge have long been called “headless” and deemed valueless by many. As a result swordsmiths took extra care in making the kissaki.

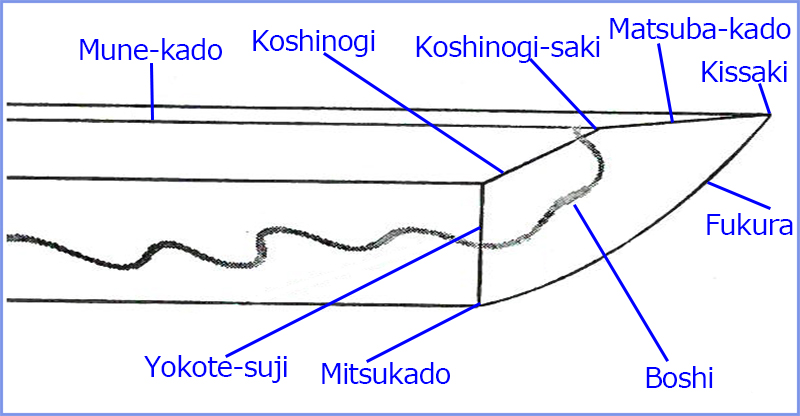

The kissaki is that important in the evaluation and authentication of nihonto, and from a practical viewpoint its sharpness and ability to cut are vitally important. The importance of the kissaki can be seen in the names given to all the different parts in an area of a mere few centimeters.

As you can see from the diagram below, there are many different parts that make up the kissaki, considering this is all in the space of a few centimetres it should give an indication as to how revered the kissaki was. From these many parts the fukura and boshi were particularly singled out by both craftsmen, appraisers and collectors.

To describe the fukura, people would use words like “kareru” (withered) or “tsuku” (attached). A fukura that has a nice round curve sticking out is called a “fukura-tsuku”, whereas a fukura that does not have much curve and is closer to a straight line is called “fukura-kareru”. One with no curve at all is called “kamasu-kissaki”. Kamasu-kissaki were made in the beginning of the Heian period, albeit for a short period of time.

The shape of the kissaki is divided into “o-kissaki”, “chu-kissaki”, and “ko-kissaki” (large, medium, and small).

The large o-kissaki (sometimes dai-kissaki) are seen often in swords made during the North-South Dynasty Period (1336-1392) and Keicho and Genna eras (1596-1624) during the Edo period, when many smiths copied the style of the NS Dynasty swords. As expected, the chu-kissaki is the most standard pattern and is in fact the basis of today’s standard bokuto. It has a great balance, with the top area of the sword only slightly narrower than the lower area. It is seen throughout many different eras, in all regions of Japan, and in all schools of swordsmanship. The ko-kissaki were made a lot during the late Heian to early Kamakura periods, and these can also be seen in the new Kanbun swords of the Edo period.

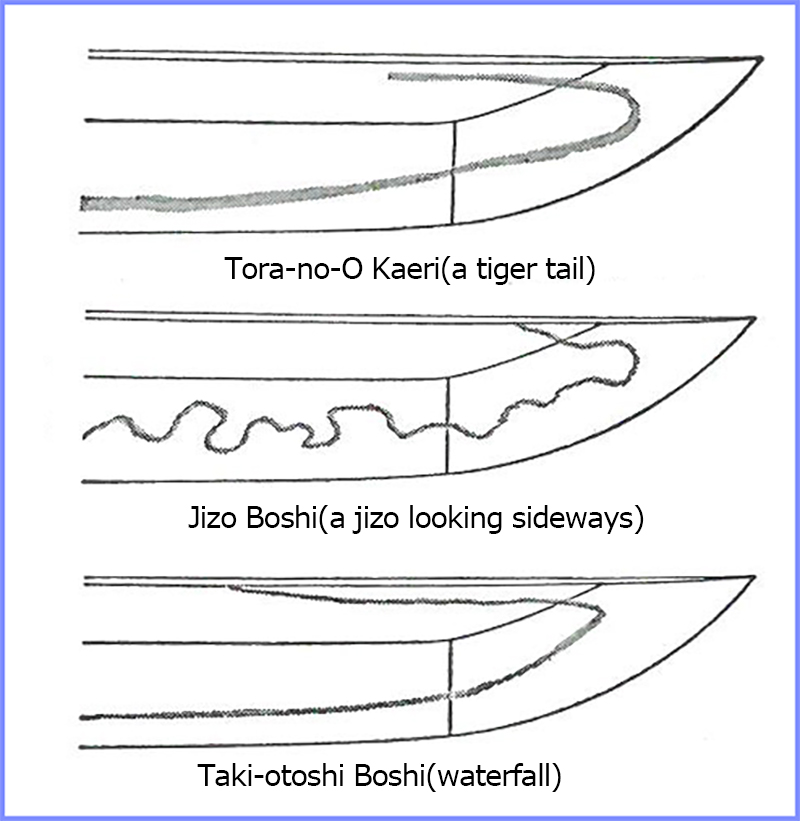

The hamon on the kissaki is called “boshi”, this part shows the skill and characteristics of the swordsmith and has great attention paid to it during authentication. These boshi can be divided into straight blades and rough blades: in general older swords have rougher blades and the new swords have straighter blades. Some of them have trendy styles and names, like the “jizo-boshi” which looks like a jizo (buddhist statue) looking sideways, or the “tiger’s tail” which, unsurprisingly, looks like a tiger’s tail.

Today we just looked at the kissaki, but the Japanese sword has so many parts with their own individual characteristics which are important in authenticating and dating it. Yet amongst these, the kissaki is perhaps one of the most important parts of the sword. Everyone loves a pretty face!

| Did you like what you've just read? Check this out. |